What is sustainability after all?

Sustainability. We know it is important – something everyone should pursue and favour, but what are its origins, and how should we understand it?

Sustainability may be as old as human existence, even though its concept as a word with various meanings is much younger. It may also be impossible to pinpoint who first used the term ‘sustainability’. However, the concerns about natural environmental preservation in the economic circles were purportedly brought up first by a German accountant Carl von Corlowitz in the early 18th century, who was one of the first to use the term ‘nachhaltiger Ertrag’ – ‘Sustained yield’ – in the context of forest management1. Already back then, environmental preservation meant that nature needed the time to regrow if we wanted to use it sustainably.

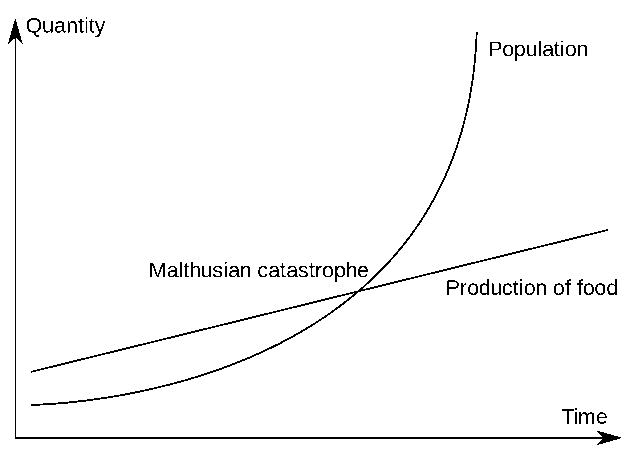

Around the same time, an English economist Thomas Robert Malthus postulated that the environment has limits 2. He suggested that as the population grows, there would be diminishing food supply per capita, leading to lower living standards, eventually ending the growth (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Malthusian curve

However, the shortcoming of the Malthusian theory was that the total production curve was kept fixed. Malthus was unable to predict that the Industrial Revolution would enable a significant shift upwards in the production curve, which is why the human population has grown from about 800 million in 1750 to nearly 8 billion at the present day.

After the first half of the 20th century, various United Nations administrators, governments and scientists started sounding the alarm bells again about the limits3. However, it was not until 1987 when the Brundtland Commission Report mainstreamed the term ‘sustainable development’ and defined it as:

“development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs”

Arguably, this is still one of the most accepted definitions for sustainable development. But what does it mean if we really try to understand it? Some could argue that the definition is elusive, which may also be one of the reasons for its wide acceptance. After all, the definition leaves much room for us to interpret and adjust it in ways that best suit different purposes.

Be that as it may, ten years after the Brundtland Commission Report, academia alone had produced over 300 different definitions of sustainability and sustainable development 4. Probably, due to a plethora of definitions, most of us have little understanding of what these terms mean.

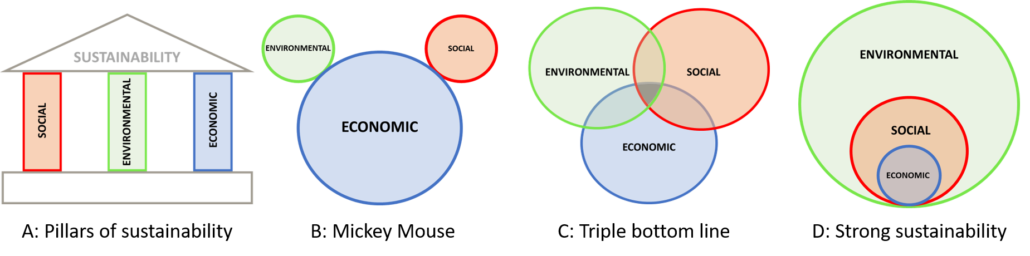

Perhaps, from the practical point of view, it makes more sense to view sustainability as a framework rather than debating its definition. In this regard, there appears to be a consensus that sustainability comprises economic, social and environmental dimensions, which the English author John Elkington coined as the Triple Bottom Line (TBL) in the 1990s. Since its introduction, many businesses have adopted TBL at least as an accounting framework to communicate their non-financial impacts. Yet, many interpretations exist on how these dimensions should be understood and promote sustainability. In this regard, some general perspectives on sustainability are coined into specific models (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Often used models that conceptualise sustainability. Adapted and modified from Peet (2009)

Many of us from management disciplines have seen representation A, where the three sustainability dimensions are presented as pillars. The fundamental message of this view is that the dimensions need to be in balance to prevent sustainability from collapsing. This conceptualisation may also make it clear to understand that sustainability issues can be discussed and addressed separately.

The so-called Mickey Mouse model (B) also sees the sustainability dimensions as separate entities. This perspective focuses on the economic dimension, where economic activities influence the other two. It is arguably not the most dominant model in terms of how we want to view sustainability. However, it has been argued that this view underpins much of the current global economic and political decision making 5.

Then there is the TBL model (C), introduced by John Elkington, according to which sustainability is achieved when a balance exists in the intersect of the dimensions. Twenty-five years after its introduction, Elkington himself 6 has, however, started to doubt whether his model has been understood appropriately by businesses. Indeed, it seems many companies have interpreted the model as a “balancing act” where trade-offs between the sustainability dimensions are possible.

Finally, the strong sustainability model (D) views the human world as an integral environmental dimension. It recognises that social and economic systems exist as subsystems of the wider ecosystem, ultimately setting limits to growth. Therefore, strong sustainability can only work if the natural environment is sustained and human impact within it is manageable. 7

However, economic growth has dominated our current ways of living. This growth has enabled better infrastructure and higher life expectancy, positively contributing to our wellbeing. Hence, economic growth should not be seen as bad as such. However, the excessive economic growth stemming from our current lifestyles promotes increased material consumption, which has led to the depletion of the natural world and issues like climate change. The world has become a human-centric place, where strong sustainability seems impossible. 5

Should we, however, feel doom and gloom about our planet when we have governments and businesses committing more and more to sustainable development? After all, we read more news every day about innovations that will make life more sustainable in the future. Such innovations include lab-grown meat that grows in Petri dishes currently but will become available in grocery stores in the future. Sustainable development is also taking place in the fashion industry, where many fashion houses have started to add recycled materials into their textiles. These are only some examples that demonstrate that we are heading in the right direction. Therefore, we should stay optimistic. Right?

However, we should also realise that, in a way, the future is now and not tomorrow. After all, the actions and decisions we make today have consequences on our tomorrow. And unfortunately, due to human-induced climate change, the future will be unequal for us – especially for those living on ice or in coastal regions – let them be polar bears or humans. Let us also ask ourselves: Do we have that lab-grown meat in our local grocery stores now? The answer is no, and while we are waiting for it to become available, the world is consuming meat and dairy more than ever, which produce about 14.5% of global CO2 emissions8. And while the fashion industry is blending more recycled materials into their clothes, the average consumer also buys 60% of more pieces of clothing today than 15 years ago, and each item is kept for half as long, of which the majority ends up in landfills9.

To conclude, even though we see evidence of sustainable development, can we call this development sustainable in the big picture, within the limits of growth? The answer to this depends mainly on how we understand sustainability. Arguably, as a word, ‘sustainability’ holds different meanings to different people in different contexts. These meanings are not static either and are subject to alterations when various actors such as governments, scientists and business representatives communicate about it. Having said this, we should take the responsibility seriously for how we teach and communicate sustainability to others – even as an abstract concept. Although we may all have somewhat differing views on sustainability, we can still find ourselves sharing perspectives with some of the models presented in this blog post. The question is, which of the models do you wish yourself and the others to be advocating – the strong sustainability or the Mickey Mouse?

Written by Eljas Johansson, Gdańsk University of Technology

References:

- Grober U. Deep Roots: A Conceptual History of “sustainable Development” (Nachhaltigkeit). Vol No. P 2007.; 2007. https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/50254/1/535039824.pdf

- Zeder R. The Malthusian Theory of Population. Published 2020. https://quickonomics.com/the-malthusian-theory-of-population/

- Bansal P, Song HC. Similar but not the same: Differentiating corporate sustainability from corporate responsibility. Acad Manag Ann. 2017

- Johnston P, Everard M, Santillo D, Robèrt KH. Reclaiming the definition of sustainability. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2007;14(1)

- Mulia P, Kumar Behura A, Kar S. Categorical Imperative in Defense of Strong Sustainability. Probl Ekorozwoju. 2016;11(January):29-36. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2858188

- Elkington. 25 Years Ago I Coined the Phrase “Triple Bottom Line.” Here’s Why It’s Time to Rethink It. Harv Bus Rev. 2018;June 25. https://hbr.org/2018/06/25-years-ago-i-coined-the-phrase-triple-bottom-line-heres-why-im-giving-up-on-it

- Peet J. Strong Sustainability for New Zealand: Principles and Scenarios.; 2009. http://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&btnG=Search&q=intitle:Strong+sustainability+for+New+Zealand#4

- Kevany S. 20 meat and dairy firms emit more greenhouse gas than Germanu, Britain or France. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/sep/07/20-meat-and-dairy-firms-emit-more-greenhouse-gas-than-germany-britain-or-france Published September 7, 2021.

- UNEP. UN Alliance For Sustainable Fashion addresses damage of ‘fast fashion.’ Accessed January 17, 2022. https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/press-release/un-alliance-sustainable-fashion-addresses-damage-fast-fashion